LATEST: Overdose deaths increase by almost 30% (December 2019)

Deaths from overdose in Portugal increased by almost 30 percent in 2018 and reached their highest figure in the last five years, with most cases involving more than one substance. The SICAD reports highlighted in these overdoses the presence of opiates (65 percent), cocaine (51 percent) and methadone (31 percent), highlighting the increase in cases with both opiates and cocaine. In the vast majority (92 percent) of overdoses, more than one substance was detected, with alcohol (45 percent) and benzodiazepines (20 percent) standing out in association with illicit drugs. As for the other causes of deaths with the presence of drugs (258), they were mainly attributed to natural death (42 percent) and accidents (38 percent), followed by suicide (14 percent) and homicide (3 percent). READ MORE

Hospitalizations for psychotic breakdown or schizophrenia in patients with registered cannabis use have increased almost 30-fold over the course of fifteen years in Portugal. This is the conclusion of a study by a group of researchers from the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Porto (FMUP) and CINTESIS – Center for Health Technology and Services Research. The study, published in the International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, analyzed hospitalizations in all public hospitals in mainland Portugal from 2000 to 2015. In total, the research team recorded 3,233 hospitalizations, which ranged from 20 hospitalizations in 2000 to 588 hospitalizations identified in 2015. “If we consider all hospitalisations due to psychotic breakdown or schizophrenia, we conclude that in 2015, more than 10% of these cases corresponded to patients with a secondary diagnosis of cannabis use, while in 2000 they were less than 1%,” says Manuel Gonçalves-Pinho, physician, CINTESIS researcher and author of this work. READ MORE

Attempts to legalise marijuana in Portugal (Jan 2019)

Political parties in Portugal are now pushing for the legalisation of marijuana in their country because they wrongly believe it will combat current problems around organised crime, drug trafficking, increased consumption and the use of psychoactive substances. The Left Bloc (BE) and People-Animals-Nature (PAN) are proposing legalisation of cannabis for recreational use, with two bills tabled to the Portuguese parliament. According to statements made to the local media by Portugal’s Association of Studies on Cannabis, the regulation would draw “people off the street“, avoiding their using “a substance in a hazardous, unhealthy place, in contact with dangerous people related to drug trafficking, where there is absolutely no control over the quality and toxicity of the product,”. It would also constitute “a major step towards taking the business away from organised crime groups.” They say that the effect of decriminalisation has been to increase trafficking and consumption every year, which has been shown to have failed across the board.

READ MORE

Portugal Mayor supports recriminalising public drug use (October 2019)

Yet just last month, the mayor of Porto contradicted his previous pro-harm reduction position and endorsed reintroducing criminal penalties for drug use in public spaces. The mayor said he was “a little tired of hearing just about the dignity” of people who use drugs, adding that the policy of decriminalisation “simply does not protect the overwhelming majority of the population,” giving as an example the people who, in the most troubled areas of Porto, “cannot go to the window because they are threatened“. He is advocating for the installation of over 100 new video surveillance cameras to monitor public streets in an attempt to clamp down on drug use. “It is necessary to criminalise, nobody is arrested for an offense,” he said.

Portugal’s drug decriminalisation in 2001 is touted as the positive example New Zealand should aspire to. The basis for such a proposition was based on a 2009 report by the libertarian think tank, the Cato Institute. But the report has been shown to have many shortcomings and weaknesses.

Basically, decriminalisation did not trigger dramatic changes in drug-related behaviour because, as an analysis of Portugal’s pre-decriminalisation laws and practices reveals, the reforms were more modest than suggested by the media attention they received.

In 2010, the Obama Administration essentially dismissed the Cato report stating it was “difficult, however, to draw any clear, reliable conclusions from the report regarding the impact of Portugal’s drug policy changes.”

The reports limitations included:

* supporting analysis not definitive – sometimes focusing on prevalence rate changes as small as 0.8%.

* fails to recognize other factors – the report attributes favourable trends as a direct result of decriminalisation without acknowledging, for example, the decline in drug-related deaths that began prior to decriminalisation.

* adverse data trends not reported – adverse social effects – such as the increase in drug-related deaths in Portugal between 2004 and 2006 – is sometimes ignored, downplayed, or not given equal recognition.

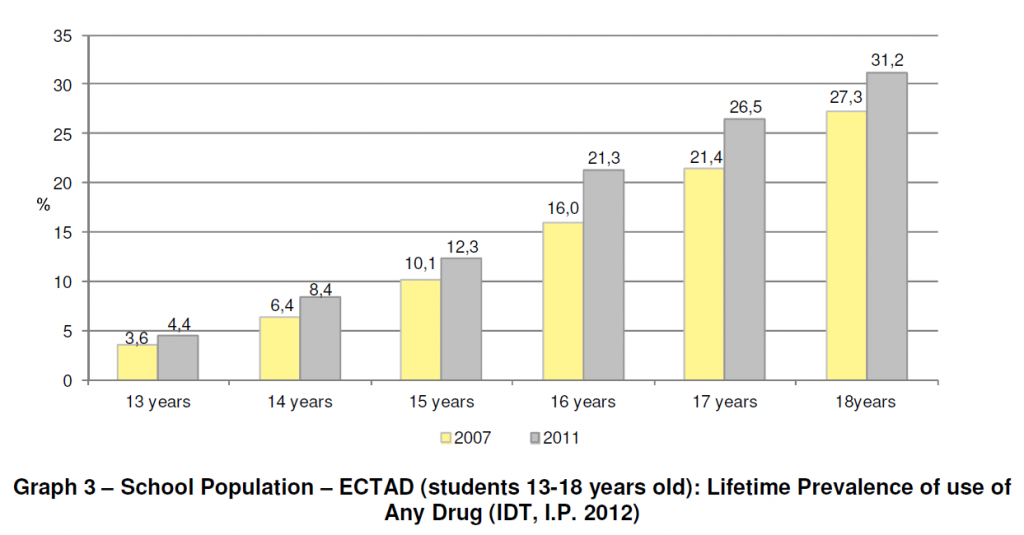

* core drug‐use reduction claims not conclusive – as “proof” of drug legalisation’s success, the report trumpets a decline in the rate of illicit drug usage among 15- to 19- year-olds from 2001 to 2007, while ignoring increased rates in the 15-24 age group and an even greater increase in the 20-24 population over the same period. In a similar vein, the report emphasises decreases in lifetime prevalence rates for the 13-18 age group from 2001 to 2006 and for heroin use in the 16-18 age group from 1999 to 2005. But, once again, it downplays increases in the lifetime prevalence rates for the 15-24 age group between 2001 and 2006, and for the 16-18 age group between 1999 and 2005.

Additional Studies Offer More Contradictory Evidence

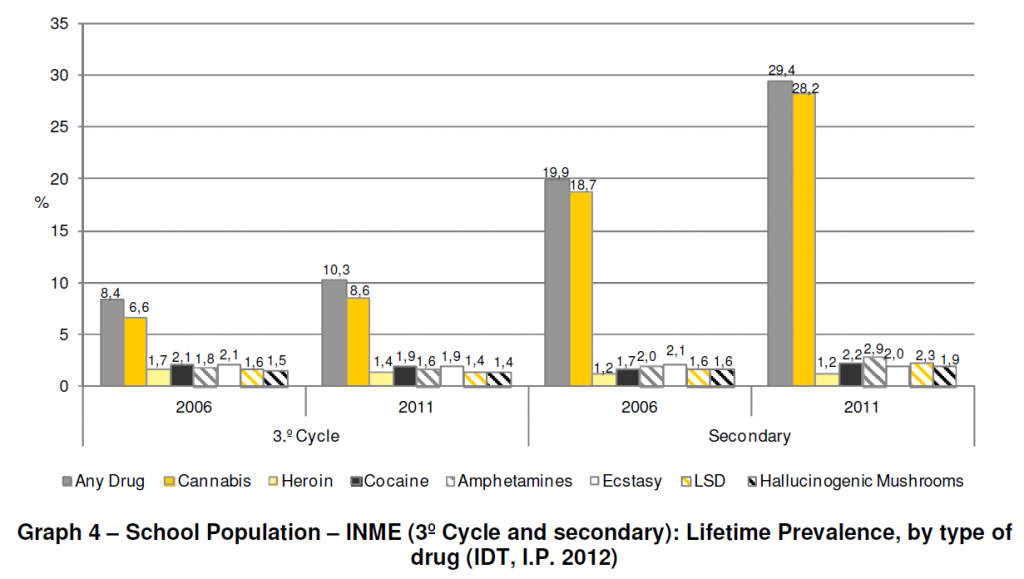

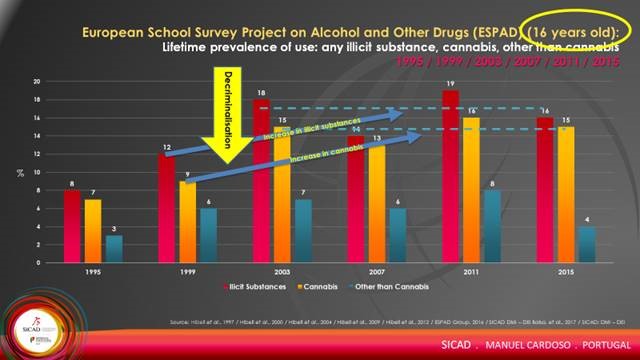

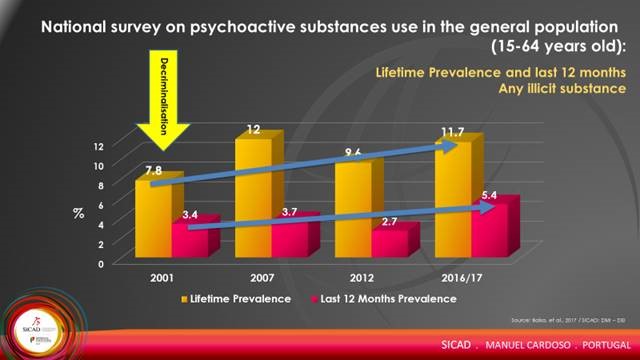

Statistics compiled by the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) indicate that between 2001 and 2007, lifetime prevalence rates for cannabis, cocaine, amphetamines, ecstasy, and LSD have risen for the Portuguese general population (ages 15-64) and for the 15-34 age group.

Although high-school student use fell from 2001 to 2007, it rose steeply from 2006 to 2011. This included cannabis, amphetamines and ecstasy.

Drug-induced deaths, which decreased in Portugal from 369 in 1999 to 152 in 2003, climbed to 314 in 2007 – a number significantly higher than the 280 deaths recorded when decriminalisation started in 2001.

UPDATED: Statistics just released

Between 2012 and 2017 Lifetime Prevalence statistics for alcohol, tobacco and drugs for the general population (aged 15-64) have risen by 23%. The study saw an increase from 8.3% in 2012, to 10.2% in 2016/17, in the prevalence of illegal psychoactive substance use.

“We have seen a rise in the prevalence of alcohol and tobacco consumption and of every illicit psychoactive substance (affected by the weight of cannabis use in those aged 15-74) between 2012-2016/17.”

Last-12-months-use of any illicit substance has doubled between 2012 and 2017!

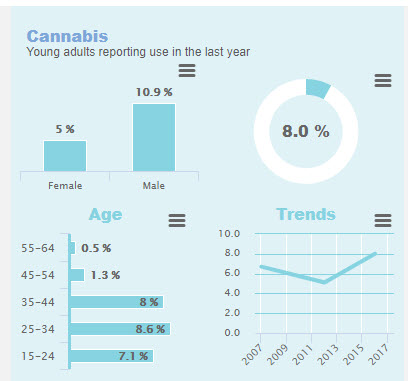

Estimates of last-year drug use among young adults (15-34 years) in Portugal (2018)

SOURCE: – European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA)

“Claims that decriminalisation has reduced drug use and had no detrimental impact in Portugal significantly exceed the existing scientific basis.”

Gil Kerlikowske, Director, US Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP) Source: Personal letter cited in Manuel Pinto Coelho, Op. Cit., 2010

“A thorough report in 2011 by the European Monitoring Center for Drugs and Drug and Addiction (EMCDDA) presented a more nuanced picture. EMCDDA concluded that Portugal’s drug policy of depenalisation is not a “magic bullet” and that “the country still has high levels of problem drug use and HIV infection, and does not show specific developments in its drug situation that would clearly distinguish it from other European countries that have a different policy.”

UNODC (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime): Cannabis A Short Review (2012)

“Our drug problems are not solved.”

João Goulão, director-general of SICAD: the Centre for Intervention on Addictive Behaviours and Dependencies. Known as Portugal’s ‘drug czar’.

“There is a black market – “people don’t know what they are buying, what they are selling” – the system “is confusing”, with many people believing that decriminalisation means that drugs are legal.”

Adriana Curado, project coordinator at the GAT Harm Reduction Centre

“If it was not so troublesome to be a drug dependent, I am sure that I would not have cured myself. If I knew that it was easy for me to get my drug of choice with-out any worries, I am positively convinced that I would not be able to stop using it ever. Drugs are like that.”

Sandra – former drug dependent

It is also significant to note that Portugal recently voted down a bill proposing to legalise medicinal – including grow-your-own – cannabis, and opted for a more confined law allowing use of some medicinal cannabis.

Portugal coerces treatment and rehab, as does Sweden which reduced its drug use from the late 1970s from the highest levels in Europe to the lowest in the developed world by the early 1990s.

To summarise (courtesy of Drug Free Australia):

• Decriminalisation has increased drug use for all age-groups

• Decriminalisation has seen sharp increases amongst high-school students

• Portugal’s drug use, other than for heroin, was initially lower than European averages

• It is not clear what caused major decreases in opiate use before decriminalisation

• While drug deaths in Portugal are much lower in Portugal due to heroin being smoked or snorted rather than injected, drug overdose mortality is currently increasing

• HIV decreases are mostly not due to decriminalisation

READ MORE DETAILED ANALYSIS

Dalgarno Institute (Australia): Portugal Drug Policy – A Review of the Evidence

“The way that the Portugal Drug Policy model is ‘spun’ has more to do with Harm Reduction and/or Drug use acceptance than anything else. The current ‘positive’ (evidence and outcome ignoring) interpretation/ implementation /promotion of the Portugal Drug Policy model does not facilitate Best-Practice – Demand Reduction/Prevention (Deny or delaying uptake of illicit drugs – building resiliency into the community). Nor does it actively facilitate drug use exiting recovery from illicit drug use. Again, its tenure is more focused on ‘net community benefit’, attempting to manage the damage (and enabling of sustained/ongoing drug use) and consequently it inadvertently fosters the normalisation of an illicit drug using culture.”

Drug Free Australia: The Truth on Portugal – Countering false claims by activists concerning Portugal’s decriminalisation using its own official statistics

Dr Manuel Pinto Coelho: Drugs – the Portuguese fallace and the absurd medicalization of Europe

ADDITIONAL READING ON PORTUGAL

Portugal decriminalised drugs resulting in teen use doubling in a decade

Daily Mail 31 October 2014

The nation held up by the Liberal Democrats yesterday as a shining example of how to win the war on drugs is far from the unqualified success story they make out.

For the number of children using drugs in Portugal has more than doubled since the country’s laws were liberalised, the latest figures show. A decade after the law was relaxed, nearly a fifth of 15 and 16-year-olds use drugs – well over twice the number in the years before decriminalisation.

The controversial Home Office report commissioned by the Liberal Democrats states: ‘It is clear that there has not been a lasting and significant increase in drug use in Portugal since 2001.’ But the evidence suggests otherwise.

The most recent independent report on what is happening in Portugal shows that in 1995 eight per cent of Portuguese teenagers had tried drugs.

In 1999, when laws began to be relaxed, it was 12 per cent.

But after decriminalisation in 2001, it rose to 18 per cent in 2003 and 19 per cent in 2011. The picture for cannabis use is similar. In 1995, only 7 per cent of Portuguese teens had tried the drug but by 2011 the figure was 16 per cent.

Do we really want Portugal’s drug laws?

The Spectator 18 June 2017

‘The war on drugs has failed,’ asserted Shirley Cramer, chief executive of the Royal Society for Public health in the latest propaganda coup for the pro-drug lobby. Her society, along with the Faculty of Public Health, have parroted the familiar call among metropolitan liberals for drugs to be decriminalised. Their argument is that we should drop our punitive approach to drugs and be more like Portugal, which decriminalised drugs in 2001 and now, it claims, has fewer deaths from drug use that.

There are a couple of problems with this. Firstly, drug decriminalisation in Portugal is only a success if you cherry-pick your statistics carefully. If you want to make the opposite argument you can pick a few which work in the other direction – such as pointing out that there has been 40 per cent increase in homicides related to drugs, and that HIV infection related to intravenous drug use were by 2005 the third highest in Europe.

But there is another rather fundamental problem with the Royal Society for Public Health’s argument. Britain only has a punitive drugs policy in theory. In practice, we have a softer attitude even than decriminalised Portugal. Theoretically, you can get a 7-year sentence for possession of class A drugs like heroin and crack cocaine, and five years for possession of a class B drug like cannabis. Yet in practice, British drug users can, by and large, snort and smoke with impunity. A freedom of information request in 2011 revealed that only 554 people were in jail for drug possession, and a further 3501 for possession with intent to supply. Even Harry Hendron, the barrister recently convicted of supplying drugs which killed his 18-year-old Columbian boyfriend has not been sent to jail, but was given a community sentence instead.

Get hooked on opiates, and the British state will even fix you up with methadone for free. There are now 140,000 state-sponsored methadone users, each of them costing taxpayers £3,000 a year. Is that really a ‘punitive’ policy?

British drug-users wouldn’t like the Portuguese regime – where, contrary to what some try to imply, drugs remain illegal. Those caught with drugs are hauled before a ‘commission for the dissuasion of drug addiction’. They may not get a criminal record but they can be fined, placed on a compulsory treatment programme, or even have their passport confiscated. I only wish we used such firm measures.

The pro-drug lobby likes to quote Portugal at us not because it wants Britain to copy what Portugal has done but because it counts on us not knowing what actually happens to drug-users in Portugal and hopes that, like the Times headline did on Thursday, we will confuse the words ‘decriminalised’ with ‘made legal’. The latter is what metropolitan liberals really want, not because they are especially concerned with the health of drug addicts on distant council estates but because they rather like using drugs themselves.

Decriminalisation Of Drugs In Portugal Was Not A Success, Says Dr Manuel Pinto Coelho

Huffington Post 10 Dec 2012

…despite his country’s policies being lauded, Dr Manuel Pinto Coelho, President of the Association for a Drug Free Portugal, says decriminalisation has not worked. “Decriminalisation in Portugal was not a blessing. Decriminalisation didn’t help us. It was decriminalisation that results like this? I don’t know. It makes no sense that people say since decriminalisation drugs use fell in Portugal,” he told The Huffington Post UK, citing statistics from the White House which show an increase in drug related deaths between 2004-2006 in the country. Dr Pinto Coelho argues that viewing drug attacks as sick means the line between dealers and consumers is blurred. “There is now in Portugal a trivialisation. It is more trivial then it was before. I’m not happy with this,” he said.

“I don’t believe a society where people have addiction is part of life. There are people who are happy in the system, I believe in the treatment in the drug dependents and that it is possible to put a final part in their addiction. I believe that every system, every policy system, should have a final goal; life without drugs. I believe they can reach a life without drugs, I believe we have always to have to fight against cancer and poverty and unhappiness and hunger and drugs.” According to statistics compiled by the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) between 2001-07, after decriminalisation, more people took cannabis, cocaine, amphetamines, ecstasy, and LSD – but decreased in neighbouring Spain between 2003-2008. “Kofi Annan said a very interesting thing – the eradication of drugs in our planet is a difficult task but we can go forward, we can go through it. Since decriminalisation in Portugal there was an increase in every single drug. In cannabis and cocaine and ecstasy and in HIV aids,” he said.