Legalising cannabis as a move aligned with history’s progress is beginning to crack, at least in the United States.

A referendum campaign is gaining momentum in Massachusetts to overturn the state’s 2016 legalisation of recreational cannabis. This comes amid new research indicating a rise in young cannabis users presenting at hospital emergency departments. This isn’t the only US state to psuh back against legalisation. Other US states such as Maine, Florida and North Dakota and South Dakota have shut down legalisation ballot initiatives, with Idaho set to vote on stronger cannabis prohibitions next year.

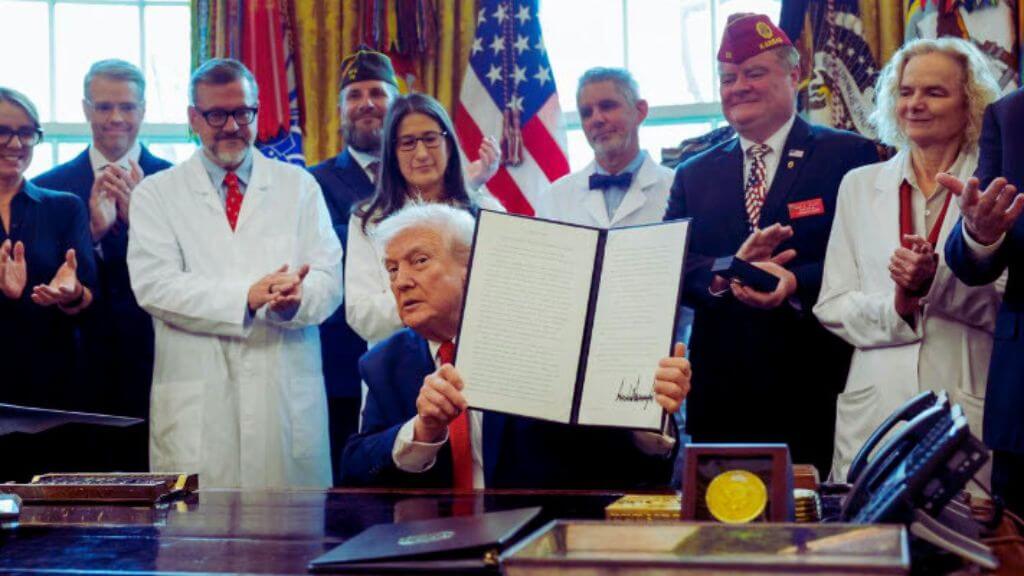

Even the US Congress, on a bipartisan basis, passed legislation quietly re-banning a type of cannabis that had been legal nationwide for nearly a decade. The nationwide ban on all kinds of THC comes into effect next year, meaning Americans will, for the first time since federal prohibition in 1937, have less access to cannabis than they previously did.

Since California legalised medical marijuana in 1996, momentum toward liberalisation has appeared relentless. Recreational marijuana is now legal in 24 states and Washington, D.C., with a further 15 states allowing medical use. Public support rose steadily from around 25 per cent in the late 20th century, reaching a majority in 2011 and peaking at 70 per cent in 2023—including majority support among Republicans. Political leaders and activists confidently declared the issue “settled” and “on the right side of history.

For years, cannabis legalisation was seen as inevitable. However, that trend is now showing signs of reversal, with a significant drop in Republican support for the first time since 2016, and even in public support. What once seemed to be an unstoppable cultural movement is showing signs of public reconsideration—suggesting that legalisation persisted not because it was wise or harmless, but because it was regarded as beyond debate.

Interestingly, most Americans neither use cannabis nor have a personal stake in the issue. A 2024 Pew poll shows support for recreational legalisation is about 15 points lower than in other surveys. A 2022 Emerson poll, funded by the anti-legalisation group Smart Approaches to Marijuana, found only 38% supporting the legalisation of “production, recreational use and sales, like in stores,” 18% supporting just decriminalisation of possession, and 30% advocating only for medical use. It seems that while many Americans support legal cannabis in theory, they often prefer it not to be present in their local communities.

For years, cannabis legalisation was presented as inevitable in New Zealand, following the same overseas script that framed reform as “progress” and resistance as outdated. By the time of the 2020 cannabis referendum, voters were told that legalisation was simply the next step on the right side of history.

New Zealanders disagreed. Despite heavy campaigning and cultural pressure, the public voted no—sending a clear message that the wellbeing of families, children, and communities mattered more than ideological momentum. That decision now looks increasingly prudent as overseas jurisdictions quietly confront the unintended consequences of liberalisation, from increased exposure for young people to growing concerns about mental health and community harm. Far from being left behind, New Zealand showed that careful restraint—grounded in protecting the vulnerable—still resonates when voters are trusted to weigh the real costs.

More Americans are realising that the promises of legalisation were overstated and its costs were underestimated. This was evident in the 2020 Cannabis referendum in New Zealand, where most voters saw through the facade and voted no to cannabis legalisation. That choice now seems increasingly wise as other countries quietly face the unintended effects of liberalisation, including greater risks for youth, mental health issues, and community damage. Rather than falling behind, New Zealand demonstrated that restraint—focused on safeguarding the vulnerable—remains powerful when voters are trusted to consider the true costs.

So as more US states consider banning what is widely recognised as a harmful drug, we welcome this shift in attitude and policymaking. It’s also encouraging to see international contexts recognise that legalisation isn’t the perfect solution it’s sometimes portrayed to be, and that prohibiting harmful drugs is becoming an increasingly accepted and normal response by governments and society.

*Written by Family First staff writers*